The first Peace Festival was held in August 2017 in Cartagena de Indias on the Caribbean coast of Colombia, bringing together 30 peace activists from 16 different organisations, half from Peru and half from Colombia, in order to share their diverse approaches to constructing memory, discovering truth, and moving towards reconciliation.

On Tuesday, April 10 2018, at the Watershed in Bristol, the Peace Festival research team screened a film documenting the festival for the first time: “The film shed light on some of the creative ways these “memory activists” help their communities to construct collective narratives.” (Bristol Latino, 2018)

Goya Wilson, form the University of Bristol team explains: “The Peace Festival mapped the existent diverse experiences in Peru and Colombia, and invited activists from both countries to enter into dialogue and reflect on the challenges they face, and to learn from one another based on their experiences, materials, histories, lessons, and practices.”

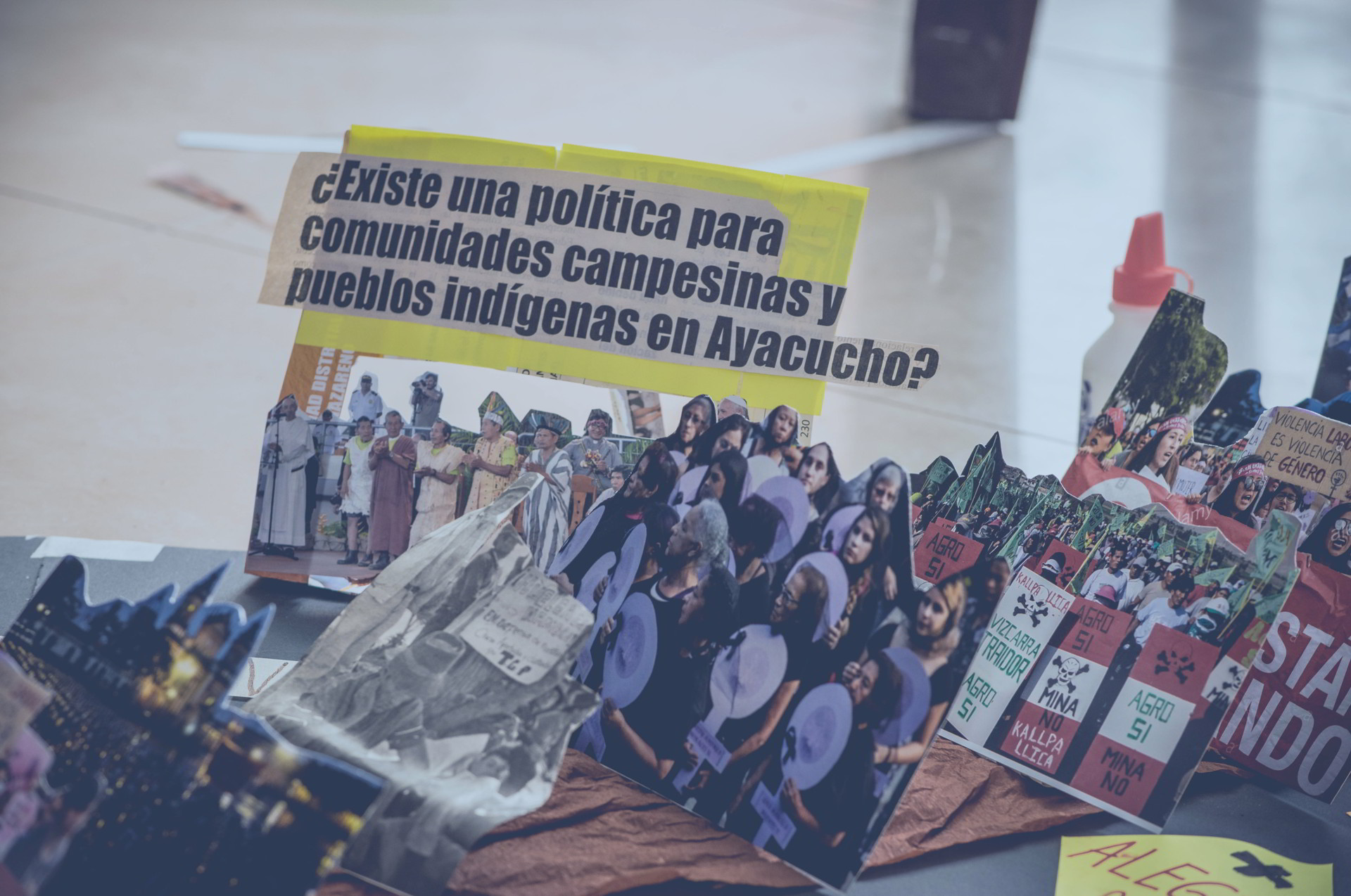

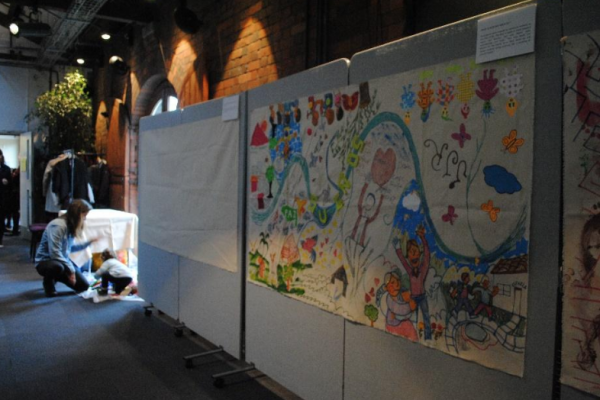

The evening also included an exhibition of the art produced by the participants, with guided tours of the exhibits by the team. From the entrance of the room you could see hanging from the ceiling the different creative representations of each collective or organization.

There were four murals that were created collectively during the Peace Festival event responding to four different questions:

What can memory achieve? How do we do memory work? What is memory made of? What are the obstacles of doing memory work?

Participants took the question and decided to represent their memories as a wall covered in climbing plants.

They chose a flower charged with meaning. “La cantuta” is not only Peru’s national flower but also the symbol used by activists and relatives of students that were killed under Fujimori’s regime.

Participants chose ‘Tulpa’ as a symbol for their canvas. Tulpa refers to the rocks surrounding a fire and to the community that gathers around that fie to share their stories in order to remember their loved ones with objects, photographs, and texts. Several hands and paths criss-cross and intertwine in this and all memory-work.

“In one large mural, a river of sueños (dreams) was chosen to represent memory: evocative of death, pain, remembering and hope. The participants reflected that “the river feeds our dreams for the future”. (Bristol Latino, 2018)

It was significant that the last mural, which corresponded to the last question about the obstacles of doing memory work, was empty. Nobody was willing to engage with this question. It was left as testimony to the challenges and silences in memory-work.

María-Teresa Pinto Ocampo, of the University of Bristol team, explained how memory workshops have allowed marginalised peoples to challenge the dominant narratives that erase their experiences from official

history. “Art, drama and poetry have opened up new spaces to tell these stories. They allow for more collaboration and exchange, and restore agency to those who have been silenced. The result is a messy plurality, which the memory practitioners see as a necessary subversion of the simplified, singular narrative.”

(Bristol Latino, 2018) In addition, there was a round table discussion with questions featuring the University of Bristol team,

María-Teresa Pinto Ocampo, Goya Wilson, Karen Tucker and Matthew Brown, and special invited guests

Alejandra Miller Restrepo (from Ruta Pacífica de las Mujeres, a Colombian NGO which was a partner of the Peace Festival) and Rosemarie Lerner (the Peruvian co-director of the University of Bristol-led Quipu Project).

Goya Wilson, from University of Bristol insisted that they also wanted to challenge the traditional approach of development interventions that think of transferring knowledge. “We considered instead a knowledge

exchange… even subverting who the experts are… and carry the project with the memory activists as protagonists and experts on memory-work. They are the ones who have developed creative methodologies for their struggles in the face of ongoing violence and repression.”

During the roundtable, the panel highlighted that the Peace Festival was also thought of as a celebration. “A celebration of their creativity and force in dealing with pain and violence, on the enormous display of imagination and strength to create new ways of doing memory and bring about change in their countries.”

About Peace Festival

Festival Cartagena Colombia

Festival Ayacucho Perú

The contents of this website do not represent the views of the funders.